Zafar Anjum, editor of the on-line journal, Kitaab, asked if he could interview me about how I got to work with Ralph Russell, from whom I learnt Urdu. Kitaab means ‘book’ in Urdu and the journal is a great source of information and comment about writers and literature across Asia. Here’s an extract from the interview.

===================

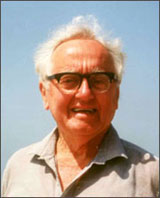

Please share your memories of working with the legendary Ralph Russell. Well, first, what made him ‘legendary’ in Urdu speaking circles? Essentially, that he was an Englishman who became an outstanding scholar of Urdu. Almost every Urdu speaker he met was astonished at the excellence of his Urdu. He spent a lot of time in India and Pakistan, and knew many of Urdu’s best known writers. He had almost mother-tongue competence – he loved speaking it, and he never stopped wanting to learn more. He was admired for the rigour of his scholarship, his skill as a translator, his ability to make Urdu literature accessible to English speakers. He had a wide appreciation of literature – not just English and Urdu – he had studied Greek and Latin literature and read a lot of European literature in translation – and he wanted people everywhere to be able to get a taste of this less well known but rich literary tradition. But what made him special to so many people was his personal qualities. He was genuinely interested in everyone he met. They sensed that, and opened up with him. He was free from any kind of prejudice. He had no interest in status, no time for personal ambition, no regard for hierarchies. He lived simply, with few material needs. He believed profoundly in equality – between people of all races, religions, genders, ages, position in society, and he met each individual on their own terms. Because of that he had an extraordinarily broad range of friendships, many going back 50 years, and he was making new friends till he died – by then of course often much younger than him. As a teenager in the 1930s he had become a communist and called himself one all his life, despite his fierce disagreements with things the leadership of the world’s communist parties did. He was direct and outspoken, but he had an ability to get onto a wave length with people of completely different outlooks. He had a great sense of humour, an enjoyment of simple things, and was an easy and delightful friend. At his funeral Francis Robinson, professor of South Asian history, summed it up by saying, ‘Ralph was a remarkable scholar, but an even more remarkable human being.’ What got you interested in Urdu poetry? I had been trying to learn Hindi on my own when I met Ralph. We were running a training course together and I saw what an exceptional teacher he was, so I switched to Urdu to learn with him. All I was aiming at was basic conversation – I had no intention of studying the literature. But I was intrigued by the way he often quoted couplets of Urdu poetry, which he would then translate for me. That was poetry as a real, living thing, and it drew me in. So I asked him to teach me some, and it went on from there. The first of his books I read was Three Mughal Poets. I recommend it to anyone who wants to find out about Urdu poetry, and that includes South Asians. Here’s how a Sindhi, Deepak Kirpalani, described its effect on him: ‘Ralph Russell’s book was unlike anything I had come across before. It combined the knowledge of an expert with the tone of a guide and the familiarity of a favourite uncle who took you as a child to the ice cream vendor or the cricket ground.’

How did you start working with him?

At the time we met, Ralph was running Urdu courses for English people who worked with Indian or Pakistani communities in the UK, as teachers, social workers etc. If anyone could get a group together who wanted to learn Urdu, he would go and teach for free. Classes started springing up in cities all over the UK and within a few years he couldn’t keep up with the demand, so he pushed some of his more advanced students into teaching alongside him. When we said we didn’t speak well enough yet to teach it, he said, ‘Just stick to the language in Part 1 of my course and you’ll be fine.’ We did that – and we discovered that teaching is a good way to improve your own accuracy!

Later he left the teaching to others so he could concentrate on his work on literature. He had always wanted to make Urdu literature accessible in translation to a wide audience, but much of what he had written had never appeared in book form. I helped him edit the books he was now producing. At the same time he was reading every draft of every story or novel I wrote. Without his steadfast encouragement I wonder if I would have had the confidence to think that anyone might want to read what I wrote. When I was having difficulty finding a publisher he dismissed it as unimportant. The important thing is to keep writing, he said – they’ll be reading you long after more fashionable writers have been forgotten. He gave the same kind of morale boost to many of his students and friends, each in their own area of work. Even if you know it’s over the top, it’s wonderful to have someone believe in you.

The first of his books I read was Three Mughal Poets. I recommend it to anyone who wants to find out about Urdu poetry, and that includes South Asians. Here’s how a Sindhi, Deepak Kirpalani, described its effect on him: ‘Ralph Russell’s book was unlike anything I had come across before. It combined the knowledge of an expert with the tone of a guide and the familiarity of a favourite uncle who took you as a child to the ice cream vendor or the cricket ground.’

How did you start working with him?

At the time we met, Ralph was running Urdu courses for English people who worked with Indian or Pakistani communities in the UK, as teachers, social workers etc. If anyone could get a group together who wanted to learn Urdu, he would go and teach for free. Classes started springing up in cities all over the UK and within a few years he couldn’t keep up with the demand, so he pushed some of his more advanced students into teaching alongside him. When we said we didn’t speak well enough yet to teach it, he said, ‘Just stick to the language in Part 1 of my course and you’ll be fine.’ We did that – and we discovered that teaching is a good way to improve your own accuracy!

Later he left the teaching to others so he could concentrate on his work on literature. He had always wanted to make Urdu literature accessible in translation to a wide audience, but much of what he had written had never appeared in book form. I helped him edit the books he was now producing. At the same time he was reading every draft of every story or novel I wrote. Without his steadfast encouragement I wonder if I would have had the confidence to think that anyone might want to read what I wrote. When I was having difficulty finding a publisher he dismissed it as unimportant. The important thing is to keep writing, he said – they’ll be reading you long after more fashionable writers have been forgotten. He gave the same kind of morale boost to many of his students and friends, each in their own area of work. Even if you know it’s over the top, it’s wonderful to have someone believe in you.

You’ve just had a book published about Ghalib. What has been the response to that, in India and abroad?

Actually it’s not my book, it’s Ralph’s, but I edited it after his death from his writing and translations. It’s called The Famous Ghalib: The Sound of My Moving Pen, and it introduces the great 19th century poet Ghalib to people who don’t know Urdu.

The response in India has been great – it has sold nearly 1,000 copies in just a few months. It definitely fills a gap – there are many books about Ghalib but Ralph had a unique ability to explain his poetry to people who know nothing about it. Yet it also works for people who do know some Ghalib, like those who might have heard his poetry sung but who can’t read Urdu. We have a UK launch lined up for October. Many people who have read Uncertain Light have told me they loved the poetry in it, and want to know more about it, so this book is perfect for them.

You’ve just had a book published about Ghalib. What has been the response to that, in India and abroad?

Actually it’s not my book, it’s Ralph’s, but I edited it after his death from his writing and translations. It’s called The Famous Ghalib: The Sound of My Moving Pen, and it introduces the great 19th century poet Ghalib to people who don’t know Urdu.

The response in India has been great – it has sold nearly 1,000 copies in just a few months. It definitely fills a gap – there are many books about Ghalib but Ralph had a unique ability to explain his poetry to people who know nothing about it. Yet it also works for people who do know some Ghalib, like those who might have heard his poetry sung but who can’t read Urdu. We have a UK launch lined up for October. Many people who have read Uncertain Light have told me they loved the poetry in it, and want to know more about it, so this book is perfect for them.

What comes easier to you – writing fiction or doing translation or editing projects like that one? Writing fiction is what fires me, and keeps me going for hours without any awareness of time passing. But it’s elusive. Fiction comes out of the air, it could be going anywhere – and typically I spend months dancing around with characters and scenarios before I really understand what my novel is going to be about; then I go back to the beginning, and start again. Non-fiction is easier because you have a clearer sense of direction. There’s an external purpose – a question I am being asked to answer, an argument I need to make, or an aspect of culture I want to explain, so there are criteria for sorting out what needs to be said. Writing practical things for my work – reports, proposals, newsletters – is how I learnt to communicate clearly, to people with little time and who knew little about the subject. That was an excellent discipline, and helped me become my own most rigorous editor – in my fiction too.

Editing Ralph’s work isn’t that different. We shared a strong desire to communicate , and my aim has always been to let his voice and intention come through as clearly as possible. Being a generation older, he had a more leisurely way of expressing things and was comfortable repeating points. He talked about wanting to write the way he would speak. That personal tone makes his Urdu language teaching materials enjoyable to use – people who have used them say they feel he’s in the room with them, talking. But styles change over time, and in his writing about literature I sometimes felt he could get his point across more effectively for a contemporary audience if he tightened up his way of expressing it, and he was usually happy to trust my judgement. Another of my roles was to point out places where he needed to write more – being so deeply immersed in the literature, he sometimes didn’t realise what needed to be explained to someone who knew very little about Urdu. I went on to edit his autobiography – a really enjoyable project – and he wanted me to be his literary executor after his death. It’s an honour to do it, and the reason I am able to is because of our 26 years working together. I hear his voice as I work with his material. I have absorbed his judgements and know which things really mattered to him.

Tell us about the poetry in Uncertain Light? How does it connect? Poetry comes into the story in two ways. The central character, Rahul Khan, grew up surrounded by Urdu poetry and he uses it to reflect on things happening in his life. Then, some of the action is set in Tajikistan, where the language – Tajik – is Persian by another name. When I first went there I would hear words I knew, because Urdu poetry derives from Persian and uses a lot of Persian words. Tajiks love poetry in the same way that Urdu speakers do, but during the Soviet period there was an attempt to break that tradition. The Persian script was banned – people were no longer allowed to read it, yet they kept it alive through memory. Now in the centre of Dushanbe, the capital of Tajikistan, there’s a statue of Sadaruddin Aini, often described as their national poet.

Almost all the translations I used in Uncertain Light are Ralph’s, but the connection is more fundamental than that. Without what I learnt from him I wouldn’t have been able to conceive of the character of Rahul Khan, nor connect with what poetry means to Tajiks. When the ideas for the story were in a very early stage we talked a lot about what it would have been like being a poet steeped in the Persian tradition but caught up in the constraints of Soviet Central Asia. Ralph was a unique source on this. Since the 1940s he had been collecting books about Central Asia, and had visited Tashkent on his way to India, where he met people who taught Urdu and Persian literature. He read with me – in Urdu translation – Aini’s reminiscences of his early life, a vivid picture of growing up in Bukhara before it was absorbed into the Soviet Union. That became one of the inspirations for the story of the fictional poet Rahman Mirzajanov in Uncertain Light.

But Ralph didn’t live to read it. Years before he died I had put it on hold, to help him work on his autobiography. I only came back to it a year after his death, and then it took surprising directions. But his spirit is there throughout.

Adapted from ‘Writing fiction is what fires me’, interview by Zafar Anjum, in Kitaab, 30 April 2016. Zafar is an Urdu speaker based in Singapore – journalist, entrepreneur, and the author of six fiction and non-fiction titles, including Kafka in Ayodhya and other short stories, and a biography of the Urdu poet Iqbal. Three Mughal Poets is published by OUP, India; The Famous Ghalib by Roli Books, Delhi. A recent English translation of Aini’s boyhood reminiscences is called The Sands of Oxus. A YouTube interview about The Famous Ghalib came out as part of the on-line LitFestX and got over 5,000 views. You can listen to it at On Ghalib. Live Q&A with Marion Molteno